New research from Livingston and Associates in NZ, funded by the Building Research Levy via BRANZ indicates the number of low- to moderate-income households with limited equity is increasing. How do we meet the needs of this vulnerable cohort? Here is the first of four papers addressing the findings of the initial research.

Limited assets or equity means people and families are excluded from public and council housing because they do not meet the very low income or other eligibility criteria. Consequently, they are trapped in a housing market that is increasingly unable to deliver secure, affordable housing.

Young working households, Māori whanau and seniors in retirement are particularly vulnerable to these conditions and their long-term secure housing outlook is poor.

These households do not have sufficient capital to access sustainable affordable housing, whether through owner-occupation or renting. Finding secure housing solutions for these households by leveraging their limited but useful assets would relieve pressure on the current rental market as well as public housing.

Previous research indicates there are a growing number of households that would benefit from low- to limited-equity housing models, including forms of ownership, secure rental or other alternative tenure forms.

The focus of this research project, Housing solutions for low to moderate income households with limited equity (funded by BRANZ from the Building Research Levy) is to build our understanding of how other comparable countries provide housing for these households, including the housing tenure models and the policy and funding settings needed for the success of these models.

In the New Zealand context, we will establish the size, characteristics and locations of these submarkets, test economic feasibility and the level of housing subsidy required and adopt a systems-based approach to build on our understanding of the opportunities to grow these models. Our focus will be to use the systems analysis to develop potential housing solutions.

This is the first in a series of research updates providing an update on the project’s initial findings. This research update focuses on some of the key trends on the composition of low- to moderate-income households with limited equity. Future updates will provide information on international research findings, interviews with New Zealand organisations working with these households and potential solutions as the research progresses.

Key terms

Definitions include:

• A “low income household” has a gross annual income of less than $50,000 per annum.

• A “moderate income household” has a gross annual income of between $50,000 and less than $100,000.

• A “stressed household” is paying more than 30% of their gross household income in housing costs. Housing costs include expenses for rent, mortgages (both principal and interest), property rates and building-related insurance

• A “severely stressed household” is paying more than 50% of their gross household income in housing costs.

• A household’s “net worth” is the sum of all their assets, less any outstanding liabilities.

• A “not owned” household is where the occupiers do not own the dwelling they live in (also referred to as “renters”).

• An “owner occupied” household is where the occupiers own the dwelling they live in.

Housing market outcomes

Households’ ability to affordably 1 pay today’s housing costs is directly influenced by the level of their income.

We have utilised Statistics New Zealand data to identify the housing outcomes and sizes of various groups of low- to moderate-income households. These include both renters and owner-occupiers across a range of age cohorts.

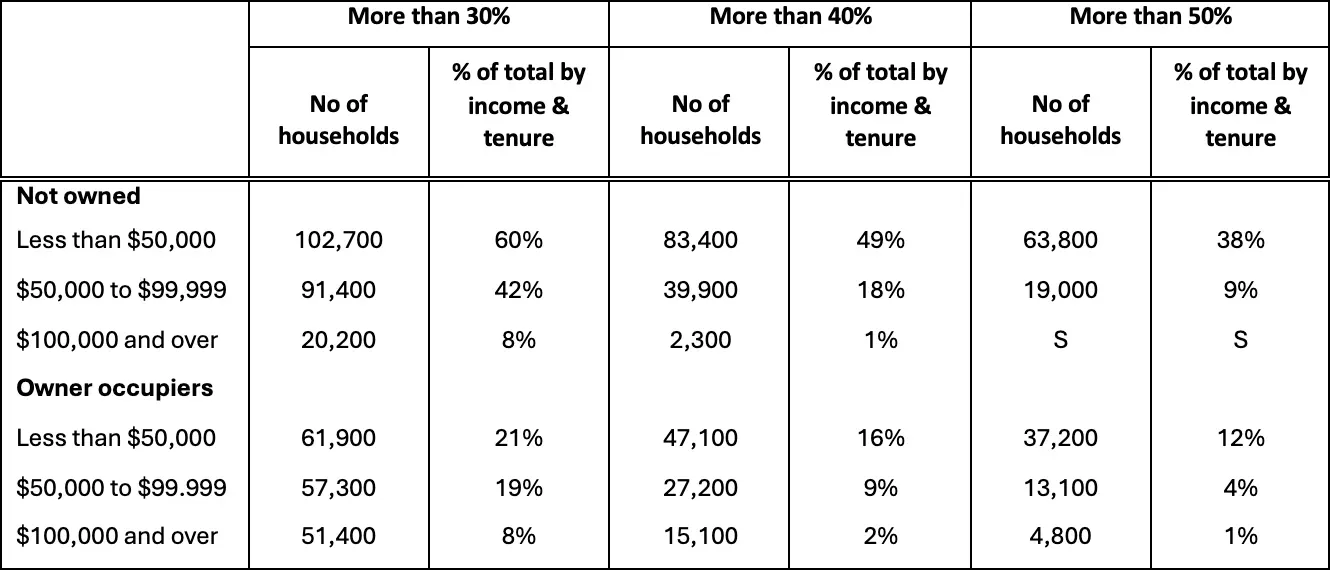

The tables below present the results of our analysis on the affordability of their housing costs and net worth.

One in four low-income 2 and one in ten moderate-income 3 renters are paying more than half their gross household income in rent. Clearly, the market is not delivering outcomes that are sustainable for these households in the medium- to long-term.

Table 1 presents the number and proportion of households, by tenure and household income, paying more than 30%, 40% and 50% of their gross household income in housing costs.

Table 1: Households paying more than 30%, 40% and 50% of their gross household income in housing costs

A total of 82,800 households that do not own the dwelling they live in are paying over half their income in rent, whereas 55,100 owner occupiers are paying over 50% of their household income in housing costs. Of these households paying over 50% of their income toward housing costs, 97% have gross incomes of less than $100,000 per annum.

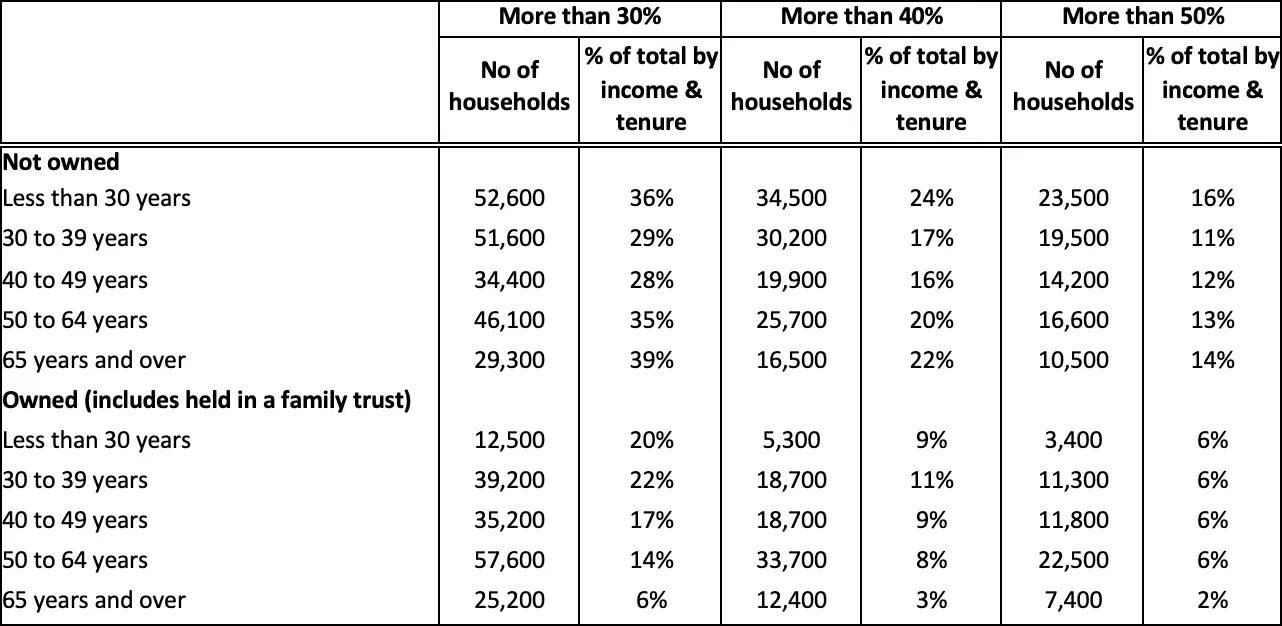

Table 2 presents the age profile of low- to moderate-income households by tenure paying more than 30%, 40% and 50% of their gross household income in housing costs.

Table 2: Low- to moderate-income households by age of the household reference person paying more than 30%, 40% and 50% of their gross household income in housing costs.

Younger not-owned households had the highest proportion of stressed households. Additionally, over one-in-four not-owned households with a reference person aged less than 30 years were paying more than half their gross household income in housing costs. Older not-owned households also had a significant proportion of households paying more than half their gross household income in housing costs, with over one-in-seven being severely stressed.

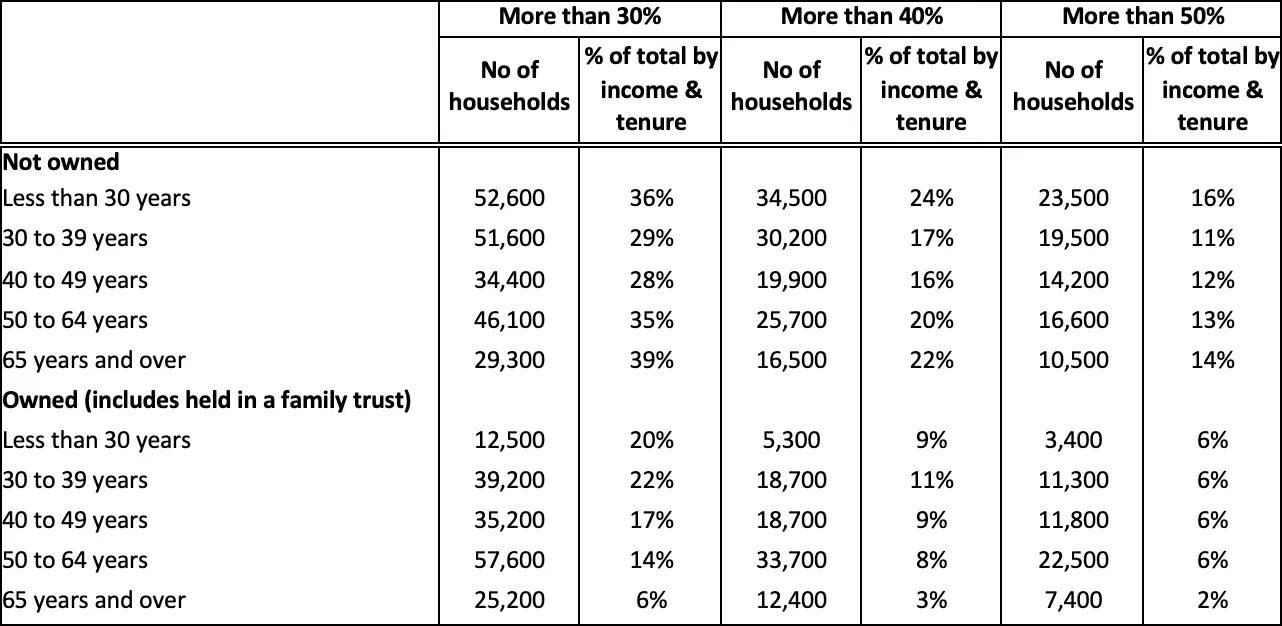

Table 3 presents the net worth (total assets less total liabilities) of low- to moderate-income households by tenure and age of the household reference person.

Table 3: Net worth of low- to moderate-income households by tenure and age of the household reference person

Even though both groups have ongoing housing expenses, not-owned households have significantly lower net worth than owner-occupied households with a mortgage of a similar age.

It would appear not-owned households have limited financial capacity to cope with a financial shock when compared to owner-occupiers.

These initial research findings clearly indicate that low- to moderate-income households are facing affordability challenges. Over 100,000 households (both owner-occupier and renters) are paying more than 50% of their gross income in housing costs. Nearly half of those households are under 30 or over 65 years old, showing significant housing stress for both younger and older households.

In addition, not-owned households have limited net worth available to draw upon should they face a financial shock. This demonstrates the importance of identifying solutions that can provide sustainable housing options matched to their incomes and net worth.

[1] Housing costs are defined as affordable when they are no greater than 30% of a household’s gross income.

[2] Low income households are those earning up to $50,000 per annum from all sources including all government benefits and the accommodation supplement.

[3] Moderate income households are those earning between $50,000 and $100,000 per annum from all sources including all government benefits and the accommodation supplement.

Share This Article

Other articles you may like