Karl Fitzgerald from Grounded puts forward an argument for growing Community Land Trusts in Australia and New Zealand, following the recent release of their new report.

Housing economics is torn between bad policy and short-term electoral cycles. If a best-practices shared equity guide was to be enacted in the current affordability crisis, one would expect a solid return on investment for any government intervention, a stabilisation of extreme conditions and a long-term aspect delivering vision.

The recent Grounded report, Grounded in Affordability: The Economic Case for CLTs demonstrates the best practices in shared equity.

Community Land Trusts (CLTs) offer an opportunity for potential residents to access the home for a 60% lower deposit, primarily because they only have to purchase the improvements, i.e. the house. They don’t have to borrow for the land. That ascertains a substantial saving on mortgage interest costs by avoiding land price interest. In its place, a smaller ground lease is paid, based on the annual municipal valuation. That saving over time is quantified at $153,000.

When a resident goes to sell, a 50% capital-gains-like tax (a stewardship fee) is paid to the Trust. A resale formula acts to ensure the asking price doesn’t outstrip median wage price growth for the area, acting in unison to deliver an affordability lock.

With these pricing stabilisers in place, a CLT could quickly become a long-term community asset.

A Land Trust is established to maintain the management of the land, to ensure it remains perpetually affordable over time. As is increasingly the case in social housing developments, project debts are paid down quickly by selling off one-third of titles to the open market.

In terms of transparency, the Trust is governed by a tripartite board of one-third residents, one-third neighbours and one-third civic-minded people. This is to ensure the board has a mix of people from both a day-to-day and a long-term perspective. It also ensures the board is not stacked by residents with a motivation to remove the affordability functions.

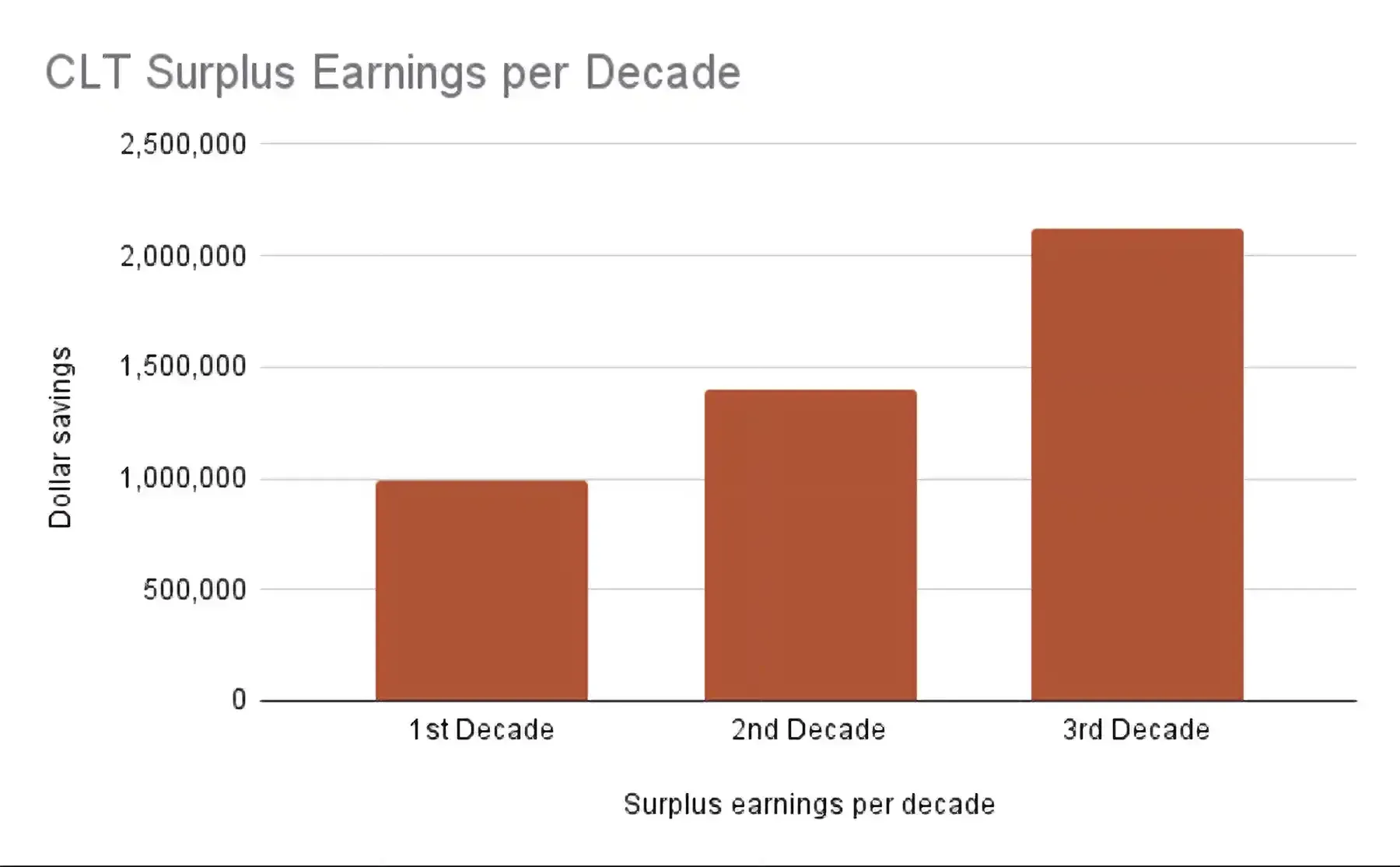

Based on a 21-home CLT development, the Trust could provide the seed funding for a new venture each decade.

With deeper networks among governments, philanthropists and superannuation, one could expect further funding to become available.

The key is the residents' ability to pay it forward i.e. to support more affordable housing. We were all brought up to believe in giving more than we take—of helping those in need, of a fair go for all—but this is absent from our property ownership culture. It is time we changed that!

This comes from recognising it is a privilege to be living on land that is essentially a commons. That sees a combination of the ground lease and stewardship fee significantly reducing capital gains (gulp!)—let’s be honest—by ensuring a 95% reduction in the capital gains one would expect in the open market. This is partly due to the affordability lock (ground lease, stewardship fee and resale formula), and partly to do with the roaring land and housing prices that have increased by 8.6% p.a.

Such a growth rate was unheard of a decade ago but, in the post-COVID era, it is seen as normal. For how long, we ask? While the returns are substantial if you have access to a super-sized deposit, how large a deposit would one need in 12 years if prices continue to increase as they have for the last decade?

The Grounded in Affordability report focuses on the regional Victorian town of Castlemaine, where land and housing prices increased by 8.6% over the decade. The affordability lock compresses that capitalisation rate down from 8.6% to 2.8%.

A CLT deposit would increase by just $16,000 to $60,000 in 12 years. A market deposit size would increase by $160,000 over that timeframe. What wage earners could save $323,000 for a deposit in a regional town? In the city, this would be closer to $437,000—just for a deposit. These numbers demand we be innovative and use best practice to offer genuine alternatives.

In light of this, would a resident be willing to gain security of tenure for a 60% lower deposit barrier? Would they then be willing to pay it forward to effectively fund 29% of a new home over 12 years? It is a big challenge to convince people of the vital need to move away from a ‘me' to a 'we’ based property ownership system.

Those in their 20s may prefer to rent the land from their community, funding more affordable homes into the future for others to find sanctuary. Those in their 50s starting over may have a 2010-sized deposit, of some $100,000. They might also value the need for new social networks, enjoying a new zest for life that cross-generational living can bring.

With mortgages now pushing 30 years, and even 40-year mortgages now being offered in Sydney, some may see it as closing the loop by leasing land off community rather than maintaining a perennial mortgage.

Please make sure you check the Recommendations section in the report, where the 23 recommendations include a simple one the Albanese government could make—to legislate the maximum length of a mortgage to 30 years. We are concerned that at current land price inflation rates, it will only be 15 years until 50-year mortgages (multi-generational mortgages) are demanded.

Part of the challenge of a CLT system is creating a viable exit pathway for residents. A practical assumption is that residents could invest a quarter of the money they save by not purchasing a market-priced home. Over a typical 12-year residency, this would see savings of some $4,000 per annum invested in an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) at 6%. When combined with a modest capital gain, a $96,000 nest egg is possible. This isn't perfect, but it offers a solid foundation for financial mobility.

Community benefits

How does the economic benefit of more affordable housing stack up for a small regional town? If we compared two 20 home developments—a CLT and a typical market development—what would the expenditure patterns look like?

| Type | Land Cost | House Coast | Monthly Interested | Annual Mortgage | Ground Lease | Interest Charged / 30yrs | Total Loan Repayments | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market | 300,000 | 250,000 | 3,298 | 39,576 | - | 637,111 | 1,187,111 | 1,187,111 |

| CLT | 300,000 | 250,000 | 1,499 | 17,988 | 4,500 | 289,596 | 539,640 | 725,083 |

The table above demonstrates the lower total cost, resulting in a $462,210 saving over the length of the mortgage. That is equivalent to an annual per household saving of $15,407 or $308,131 each year. That saving could be worth up to $9.2m per 20 homes over 30 years. This is a significant benefit to local traders, which could assist employment and growth outcomes.

| Type | Per Household Annual | Per 20 Homes Annual | Per Household / 30 yrs | Per 20 Homes / 30 yrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Economic Loss / Time | 15,407 | 308,131 | 462,210 | 9,243,930 |

When combined with the scalability of the CLT being able to provide seed funding each decade, towns that have been accosted by short-term rentals can find a pathway forward for the people who make a town tick.

Central to this is the eligibility criteria a CLT board may determine. This may involve prioritisation for key workers or long-term residents who are community-minded. Single mothers, immigrants or the environmentally-conscious could have a CLT tailored to suit. It may simply involve income thresholds based on the Area Median Income.

We expect, while the initial CLT may initially focus on an ownership model, as networks among finance and government improve, deeper funding streams will allow for a higher mix of affordable rentals.

Government programs

If we compare CLT potentials to current government-run shared equity programs, we see the programs fail best practices. Both the Victorian Home Buyer Guarantee and the Federal Help to Buy Scheme underperform on:

- One-owner program duration

- Results in subsidy loss

- Relies on next buyer paying market price

- The interest foregone on the government deposit is unaccounted for as a budget item.

- Supports demand-side purchase

- A 5% deposit enables further pricing growth, with the deposit saving used to push prices higher.

- Does little to improve supply

- New built homes can be purchased but does more to maintain a pricing floor for the developer than to encourage new ‘affordable’ supply.

The Help to Buy scheme is set to cost $6.3bn over four years, once it has been enacted with program directions. Some 25,000 first homebuyers will gain access to the funding. This is equivalent to 18% of the full homebuyers market. Some argue that is barely 5% of residential transactions.

We're concerned this program may have unintended consequences in marginal developments. It is here, where in a market that has been soft over the last year, additional demand will maintain a pricing floor.

If instead the $6.3bn was channelled towards CLTs, it could provide the land and development funding for 18,000 homes. This would deliver $91m in revenue by the fourth year of operation, in turn funding another 184 homes and growing each year. That’s the sort of ROI government should be expecting, instead of one-owner stopgap measures, or the billions wasted on demand-side incentives such as stamp duty discounts.

Geeky intricacies

Understandings around land economics are muddied at the best of times. The property lobby and their 13 various advocacy bodies (PCA, HIA, REIA, UDIA, MBA, CIE, API plus various state-based divisions of the REIA, HIA and MBA) have largely convinced the public that any tax on land or housing is passed onto the consumer.

In one of the few useful outcomes of the Falinski Inquiry, economist Saul Eslake made the following statement on p.46:

“Both economic theory and evidence suggest that a broad-based land tax, which everyone would have to pay, reduces the future value of land because there’s an additional stream of obligations associated with it, and hence would be reflected in lower land prices.”

This, when combined with the hot-potato aspect of the tax, means land supply held for future profit becomes less profitable. Over time, pressure to develop that land increases as the economic loss in terms of both stocks and flows escalates. The resultant new supply puts further downward pressure on land prices.

How does this relate to the Grounded CLT model?

A land lease is akin to a land tax. It is a holding charge on land. Growth in productivity and median wages add to land value. Alternately, land price is driven by the battle for location. The ease of finance, tax settings and speculative bidding based on expected future capital gains all contribute to land price.

A CLT focuses on land value. The land lease is based on land value. In Victoria, we have the advantage of annual municipal valuations, with the site valuation the relevant metric.

According to the Valuer General’s A Guide to Property Values 2023, Castlemaine’s median land value increased by 6.9% over the decade. A two-bedroom home appreciated by 10.3% over the decade. We took a median of both land and home price indices to find an 8.6% land price inflation rate.

To calculate how land values increase under the Grounded model, we must deduct the associated costs tied into the affordability lock. A 50% stewardship fee and a 1.5% ground lease fee bring the capitalisation rate down from 8.6% to 2.8%. This 2.8% is then applied annually as the growth metric to land values.

A 1.5% land lease is then charged on the land value plus 2.8%. Every three years, the 10-year median can be updated and applied to land values on the CLT.

With wage growth aiming to stay around 3%, this 2.8% increase in land values facilitates an affordable outcome. The Trust receives a fair return on the land, and the moderately increasing capitalisation rate deducts from the land pricing pressure felt on the open market. Importantly, land lease payments are slightly favourable to labour, enhancing affordability.

One could see the affordability lock acting as an affordability shield, protecting the CLT land from speculative interests.

Conclusion

Following the Global Financial Crisis, governments around the world earnestly announced tax inquiries so this would never happen again. Australia’s Henry Tax Review, the UK’s Mirlees report and the NZ Tax working Group all released reports finding that taxation of land was required to deter property speculation.

Little has happened since, except another almighty land bubble, increasing 52.9% since 2020, or 192.6% since 2009 (ABS 520461). The crisis is such that we can no longer wait for government to do something meaningful.

Two of the taxes discussed in the aforementioned tax reviews are utilised in the Grounded CLT model. The part land lease, part capital gains tax model aims to transition outright ownership towards stewardship. With the trajectory we are on, we might as well rent land from community rather than the nation’s largest banks.

The ACT’s Land Rent Scheme and Victoria’s Ground Lease model (see article A Provider to Follow) have improved finance’s confidence in the ability to separate land from improvements. It is time we channelled funding wasted on first homebuyers grants and stamp duty discounts towards perpetually affordable housing under the CLT model.

If we don’t get cracking now, we are only delaying it another decade when $3m homes are commonplace.

CLTs have an opportunity to demonstrate their effectiveness at a micro scale, one site at a time, building the case for what life might be like if we could curtail the commodification of land and housing throughout society.

Share This Article

Other articles you may like