Michael Thorn

Community development professional and social housing advocate Michael Thorn looks at the emerging Collective Impact approach under a much-needed critical microscope.

Since the 2010s, the Collective Impact (CI) framework has been examined as an effective community development tool and, more particularly, a solution to disconnected and uneven stakeholder participation in disadvantaged communities.

In Australia, CI has received significant attention and resourcing from both public and private sectors (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2017), achieved within a community services landscape where resources and stakeholder participation rates are limited and often restrictive. As a response to such challenges, CI has an emerging application in Australia within social housing communities, with the potential to enable equitable outcomes while minimising expenditure of community resources.

What exactly is Collective Impact?

In their article for Stanford Social Innovation Review, Kania and Kramer introduce CI as a collaborative approach toward addressing social exclusion and disenfranchisement within disadvantaged neighbourhoods. This approach involves “the commitment of a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem” (Kania and Kramer, 2011, p. 36).

Through identifying and then highlighting the desire for disparate community actors to work together for a common benefit, Kania and Kramer identify “five conditions for collective success” for stakeholders using CI:

- A common agent

- Utilisation of shared measurement systems by all stakeholders to track progress;

- Practice of mutually reinforcing activities as a way of progress;

- Continuous communication amongst stakeholders to retain cohesion during projects;

- The presence of ‘Backbone Support’ organisations to ensure the above mentioned four points are maintained.

"While CI proposes a new approach and encourages a renewed interest in community development practice, the real-time effectiveness of CI remains inconclusive."

While CI proposes a new approach and encourages a renewed interest in community development practice, the real-time effectiveness of CI remains inconclusive. Arising in the 2010s, the model remains new, so there is presently a lack of robust and comprehensive analysis of the application of CI strategies (Ninti One, 2015; Wolff, 2016; Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2017). CI also continues to receive minimal academic attention (Boorman et al., 2023).

This lack of extensive analysis of CI, despite emerging community interest, is a present contradiction in CI’s application that is worth exploring.

There are immediate economic benefits spurring this interest: CI offers social housing agencies across Australian jurisdictions an opportunity to leverage current staffing levels and resources without the need to make further significant investments or intensive staff recruitments, or the need to introduce entirely new community or place-based programs or plans. In these examples, costs are reduced by maximising the involvement of staff and other participants engaged within each social housing estate.

A cost-effective and collaboration-oriented model?

While the cost-benefit interests surrounding CI are apparent, levels of sustained participation that disadvantaged stakeholders might enjoy when the CI model becomes applied long-term are presently impossible to ascertain. Resolution to this uncertainty remains elusive, so it is this ongoing demand from local stakeholders for effective and sustainable community responses that acts as an incentive to find ways of ensuring greater levels of social inclusion.

Adjacent to this capacity of minimising both staffing and community resourcing costs, the potential for collaboration of disparate community actors using the CI framework looms as another driving factor.

CI is best understood as a practical method for coordinating efforts by community stakeholders, rather than as an overarching methodology, philosophy, or meta-narrative (Salignac et al., 2017). In the instance of social housing, CI can support tenants to articulate what is needed for the communities they reside within. However, for any community development initiatives undertaken, it is not clear how tenants can influence and assert community authority under the CI model (Romanin, 2013). Consequently, the cost-effectiveness of CI remains the prime incentive for housing agencies in adopting the model.

"Criticism centres on a lack of political literacy within the framework to address power imbalances among stakeholders."

This ‘blind spot’ of CI is an issue that has been identified within academic circles, with CI criticised for inability within its framework to address inequality between community participants (Wolff, 2016; Karp & Lundy-Wagner, 2016; Prange et al, 2016). Criticism centres on a lack of political literacy within the framework to address power imbalances among stakeholders. There is also the risk of CI-related projects becoming overly structured, and therefore, conceptually cumbersome for communities wishing to apply it. This can lead to communities trying to shape their networks and structures around a CI framework, giving the framework a teleological property, rather than using the framework to enable or develop strengths and potentials already present within communities.

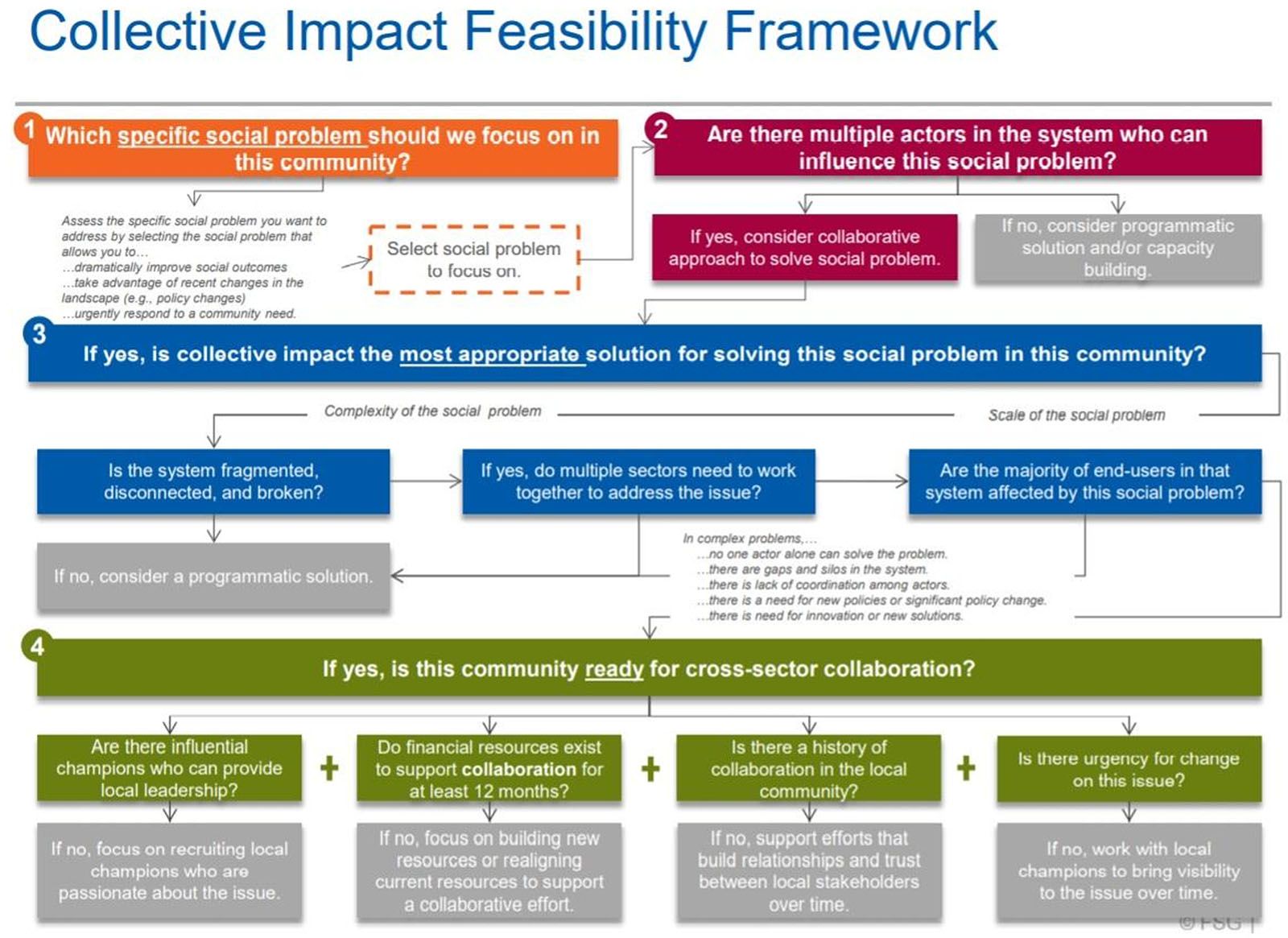

Furthermore, interpretations of CI can exist to potentially alienate community participants, as demonstrated with the, potentially excessive, schematic below:

The above diagram, which can be downloaded at the Collective Impact Forum (after signing onto the newsletter for the consultancy firm creating this diagram), is firmly directed to not-for-profits interested in pursuing CI when working with disadvantage communities. But what of the communities themselves? What is an applicable entry point for such communities interested in adopting CI? These challenges were first rigorously addressed in the report titled When Collective Impact has an Impact; the first robust study to actively examine and review application of CI within disadvantaged communities (Lynn & Stachowiak, 2018). This study examines 25 CI initiatives, interrogated across multiple settings, focus areas, and examining the implications of applying the CI framework.

"CI must be understood as a long-term proposition for communities."

While providing a much-needed evidence base, and informing further studies of this nature (e.g., Ennis & Tofa, 2020), the findings ultimately demonstrate that CI must be understood as a long-term proposition for communities. CI models should also accommodate reflexive and intermittent participation of various stakeholders. This report identifies CI as a ‘scaffold’ to build collaborative efforts within communities, rather than the presentation of CI as a prescriptive framework (Parkinson et al., 2022).

Enhancing the evidence base for CI

Extensive studies on CI are presently limited, reflecting the need for further examination of CI’s application among diverse communities. Those initiating the model are often the upper management and other executive-level stakeholders of service providers. The consequence of this top-down approach is excluding input from the very stakeholders for which the CI model has been initiated (LeChasseur, 2016; Ennis & Tofa, 2020).

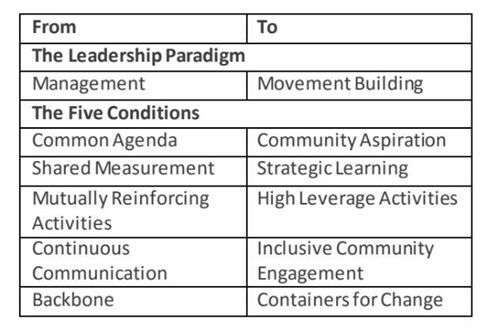

Such flaws have been acknowledged through development of ‘Collective Impact 3.0’. While this term light-heartedly likens CI to a software program susceptible to ongoing ‘upgrades’ and ‘beta testing’ per the digital parlance, the message here is of CI as an ongoing trial-and-error application process for communities (see figure below).

CI participants appear amenable to an ongoing development or ‘evolution’ of CI as a concept (Cabaj & Weaver, 2016). This enables CI to be subject to ongoing inquiry, critique, and review, allowing the framework to morph where required and introduce flexibility with co-design efforts (Preskill et al., 2014).

In Australia, dedication to the development of CI is displayed at regular national community conferences, known now as ChangeFest (Graham & O’Neil, 2014). Recently demonstrated on the international front, there is also emerging evidence of community CI projects unique to Australia (Thorn, 2018; Mission Australia, 2019; Centre for Public Impact, 2019; Allison, et al., 2020; Gwynne et al., 2022).

This is useful for social housing communities seeking inclusive methods where dissent, diversity and reflection are encouraged, and where tenants retain a sense of trust towards CI, as well as other associated community stakeholders.

It is proposed that social housing stakeholders become more aware of, not only the potential of CI as an emergent community development framework, but also the adoption of CI as part of a greater ongoing critique and improvement of community development approaches generally.

While CI does not offer magic nor permanent solutions, it does offer some renewed foundational and constructive means towards establishing ongoing collaborative practices, all needed to confront austere policy environments and reclaim community development within the public interest.

Most importantly, CI poses an immediate response to forms of ‘bricks and mortar’ social housing policy within Australia, and this requires further input within interested services, consultancies and academic circles.

References

Allison, F., Dale, A., McHugh, J. (2020), Integrating Responses to Needs and Risk of Cairns South Children and Families: Summary of findings and key forward strategies, Cairns South Collective Impact Project; The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, Qld, Australia.

Australian Institute of Family Studies (2017), written by Smart, J. (Child Family Community Australia information exchange [CFCA]), Collective impact: evidence and implications for practice, CFCA Paper No. 45, Commonwealth of Australia; Melbourne, Vic, Australia.

Boorman, C., Jackson, B., & Burkett, I. (2023), “SDG localization: Mobilizing the Potential of Place Leadership Through Collective Impact and Mission-Oriented Innovation Methodologies”, Journal of Change Management, 23(1), pp 53-71.

Cabaj, M. & Weaver, L. (2016), Collective Impact 3.0: An Evolving Framework for Community Change, Tamarack Institute Community Change Series 2016; found at: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/316071/Events/CCI/2016_CCI_Toronto/CCI_Publications/Collective_Impact_3.0_FINAL_PDF.pdf, accessed 8 September 2023.

Centre for Public Impact, written by Das, M. (published 23 July 2019), “BurnieWorks – the collective impact approach putting this Australian town back to work”; found at https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/burnieworks-collective-impact-approach-putting-australia-town-back-work/, accessed 8 September 2023.

ChangeFest: National celebration of place-based social systems change; found at https://changefest.com.au, accessed 18 September 2023.

Ennis, G. & Tofa, M. (2020), “Collective Impact: A Review of the Peer-reviewed Research”, Australian Social Work, 73(1); pp. 32-47.

FSG (2015), Collective Impact Feasibility Framework; found at https://www.collectiveimpactforum.org/sites/default/files/Collective%20Impact%20Feasibility%20Framework.pdf, accessed 10 October 2020.

Graham, K. & O'Neil, D. (2014), “Collective impact: The birth of an Australian movement”, The Philanthropist, 26(1); pp. 101-123.

Gwynne, K., Rambaldini, B., Christie, V., Meharg, D., Gwynn, J. D., Dimitropoulos, Y., Parter, C., & Skinner, J. C. (2022), “Applying collective impact in Aboriginal health services and research: three case studies tell an important story”, Public Health Res Pract., 32(2); e3222215.

Kania, J. & Kramer, M. (2011), “Collective Impact”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1); pp. 36–41.

Karp, M.K. & Lundy-Wagner, V. (2016), “Collective Impact: Theory Versus Reality”, Community College Research Centre Research Brief, No 61; Teachers College, Columbia University, USA.

LeChasseur, K. (2016), “Re-examining power and privilege in collective impact”, Community Development, 47(2), pp. 225-240.

Lynn, J. & Stachowiak, S. (2018), When Collective Impact has an Impact: A cross-site study of 25 collective impact initiatives, Spark Policy Institute, ORS Impact; Denver, CO, Seattle WA, USA.

Mission Australia (2019), Claymore Fusion Evaluation Baseline Report, Mission Australia; Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Ninti One (2017), Collective Impact: A Literature Review, Community Works; Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Parkinson, J., Hannan, T., McDonald, N., Moriarty, S., Nguyen, M., & Ball, L. (2022), “Using a Collective Impact framework to evaluate an Australian health alliance for improving health outcomes”, Health Promotion International, 37(6); daac148.

Prange, K. A., Allen, J. A., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2016), Collective Impact versus Collaboration: Sides of the Same Coin OR Different Phenomenon? University of Nebraska, Omaha, Nebraska, USA.

Preskill, H., Parkhurst, M., & Juster, J.S. (2014), Guide to Evaluating Collective Impact, FSG; found at: https://www.fsg.org/resource/guide-evaluating-collective-impact/#resource-downloads, accessed 8 September 2023.

Romanin, A. (2013), “Influencing renewal: An Australian case study of tenant participation’s influence on public housing renewal projects”, Msc. Public Policy & Human Development Thesis, 20 August 2013, Maastricht Graduate School of Governance; Maastricht, Netherlands.

Salignac, F., Wilcox, T., Marjolin, A., & Adams, S. (2018), “Understanding Collective Impact in Australia: A new approach to interorganizational collaboration”, Australian Journal of Management, No. 43; pp. 91–110.

Thorn, M. (2018), “Working Together in Claymore: An Examination of Long-Term Community Works Between Local Services and Residents”, Housing Works, Vol 13(1), pp. 28-30.

Wolff, T. (2016), “Ten Places Where Collective Impact Gets It Wrong”, Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 7(1); pp. 1-11.

Share This Article

Other articles you may like